Author: Kevin Longo

By Kevin Longo, July 10, 2017

In the warm, humid, and recently stormy summers in Windham County, in northeast Connecticut, children are enrolled in town-staffed day camps typically held at vacant elementary schools. For many consecutive years, I have presented (as a volunteer) a one-day hands-on science exhibit for the youngest children at these camps. The children have enjoyed a variety of safe and hopefully inspiring experiences over the years, including making rainbows, making lazy-susan spin art spirals with colored pencils, touching and picking up fossils and rocks to decide on their origin (animal, plant, or mineral), and trying out musical instruments such as accordions, bells, and steel guitar.

In January 2017, while on vacation, I had begun planning for my new summer science exhibits. While facing the challenge of coming up with new material, and the joy of bringing back old favorites for first-year campers, I decided to incorporate more biology into the plans, in case some students’ scientific aspirations were being left out by my emphasis on physics, geology and musical sounds. In a separate project, I had been collecting 35mm slides of planets and deep sky objects, so that campers could look through a handheld slide viewer and see the stars on their own, without suffering the freezing cold of the clear New England winter nights, nor fearing the pesky and increasingly dangerous mosquitoes and horseflies of sticky and humid summer evenings. I wondered if this viewer could be used for biology in some way.

I began to search for slide collections online with animal and plant themes, and within minutes saw a listing for 35mm slides by a woman named Claudine Laabs. I thought that this would be nice, a real collection of exotic Florida birds to study. If my summer audience of K-6 students could see the planets and stars as if they were looking through a powerful telescope, then campers could also see the birds like a birdwatcher looking through a pair of binoculars or a powerful telephoto lens. But there was something even more special about the listing. From the few sample close-ups provided by Sheila, I could see immediately that these slides were not just everyday bird pictures: rather, they were taken by someone I did not know who combined rare bird watching skill and exquisite photographic talent. Some of these shots clearly could only be taken in a one or two-minute window at the end of an entire day of waiting, planning and luck. There was a clear difference between these slides and the 1000-plus slide lots with family pictures that were in the other listings online. I had to act. I had to have these slides.

With my first shipment of slides, I began to plan how I would incorporate such antique technology into a science exhibit meant for K-6 students. I knew I couldn’t just give a lecture of my travels with a screen and a projector. They weren’t my travels to begin with, and boredom for 1960’s grandkids would be absolute naptime to 2017 internet-connected kindergarteners. I decided first to augment the atmospheric outer-space music I had used in previous shows with chirping birds and sounds of the rainforest. I gathered up a few three-foot tall artificial trees, and found a few large dinosaur figurines at my local thrift store. For the slides to work, I had to bring at least five handheld slide viewers, so that the children could take turns looking into each one and trade them with each other. I needed to keep in mind that children are working rapidly at my exhibit, so that it would be necessary to secure each slide into its viewer to prevent removal. And so this “plan” was set for my first ever biology exhibit. All that was left to do was learn about the birds in the five slides, so that my interactions would inform as well as inspire.

It was not long after January 2017 that I learned from Sheila that Ms. Laabs had also taken photographs of animals other than birds, and had in fact traveled to the Amazon River in Peru. I was fascinated by this opportunity to see what Ms. Laabs would do in this geographical region. When Sheila sold and shipped this collection to me in March 2017, I opened the box like it was Christmas and I was a child in a Dickens novel who receives but one gift. I looked in the viewer and Claudine had taken beautiful pictures of Amazon sunsets, wildlife, and birds. But added to this treasure trove of new species was a collection of pictures of the people she had met and worked alongside on her travels. There were pictures of families dressed in traditional clothing, authentic primitive living spaces, and local people and scientists holding live exotic animals. I had no idea Ms. Laabs was such a considerate and dynamic ethnographer as well as a scientific birdwatcher and photographer. If the slides activity worked as planned this year, I could use these Peru slides next year. With Ms. Laabs taking the pictures, slides could make a comeback.

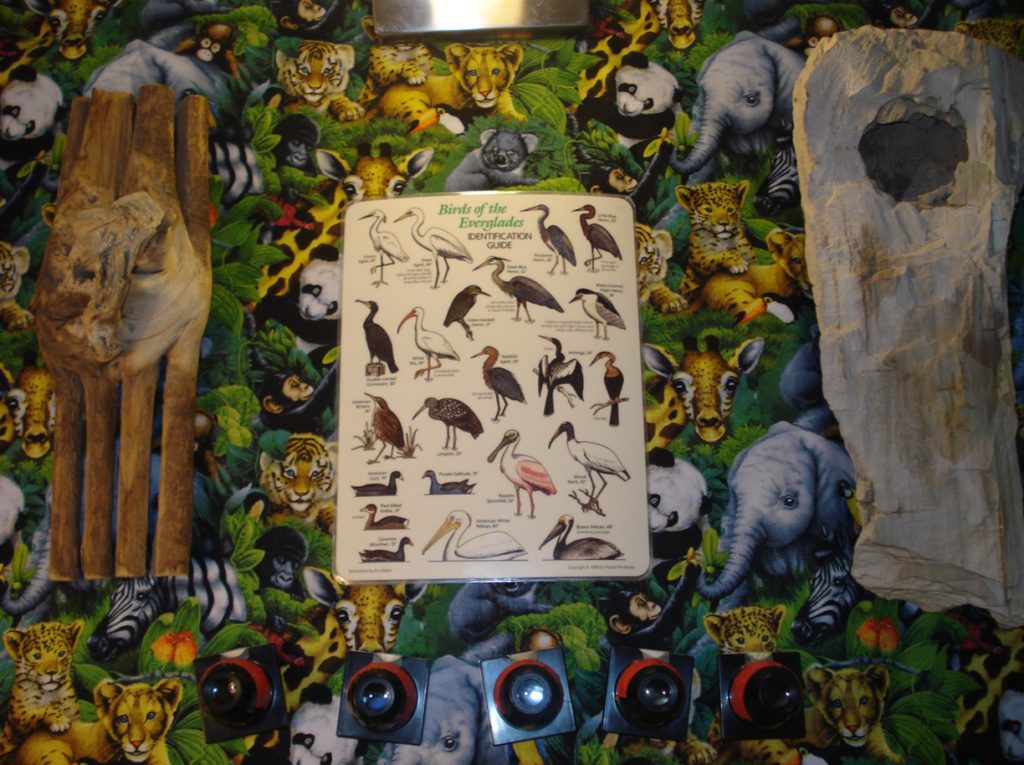

On Monday July 10, 2017, I presented this interactive science exhibit at a Connecticut town K-6 summer camp. Approximately eighty children ages 5-12 did hands-on work with fossils, fluorescent materials, musical instruments and 35mm slides. Before each group of twelve students began their work, I gave a brief explanation of each experiment, accompanied by safety and behavioral expectations appropriate for their age level. One of the activities involving slides was a display consisting of five handheld viewers, each with a preloaded and secured slide, and a laminated 8.5 x 11 poster identification guide of Birds of the Everglades (published by Florida Flair Books, 1988). The slides were telephoto lens zoom photos of the great egret, the purple gallinule, the tricolored heron, the American white pelican, and the barred owl. Approximately 70 students chose the slides activities, as there was limited time and a small number of students were too entranced by the noisemaking and fluorescent materials activities to get to each table.

The campers had amazing reactions to the slides. Many fourth graders correctly identified the American white pelican, while some identified the tricolored heron and the purple gallinule. This was a challenge because the chart showed these birds in different positions than they were on the slides. They were especially proud to have found the birds, even though they needed extra effort to carefully pronounce the common names on the chart. Many students entering sixth grade successfully took up the challenge of identifying all five birds. While I was floating from station to station, I spoke to three of these students. They had indeed found all five! The activity went as planned, and I was pleasantly surprised at the children’s enthusiasm for bird identification. The variety of birds of the everglades had had the intended effect. But the magic of the activity in a small Connecticut town was that it was made possible by Ms. Claudine Laabs.

Ms. Laabs’ 35mm slide collection consists of many binders filled with pages of 20 slides each. It is a scientific body of work and a display of rare artistic talent. Five slides does not do her work justice. But seeing so many students enjoy a small sample of Ms. Laabs’ photography made me believe that in some way, the minds of the students were for a moment in the everglades with her one late afternoon, as she handed them her binoculars or telephoto lens and encouraged them to see what she was seeing as she took the picture. That so many children saw her slides, and then took the extra step of identifying the birds she captured on film, actually convinces me that her work lives on, and that enthusiastic learners of all ages can see the rare and beautiful sights of Florida through her eyes. I hoped it was an unforgettable day for them, as it had been for me. Thanks go to the Audubon Society of the Everglades, Ms. Laabs and Sheila.

Editor’s note – Sheila Hollihan-Elliot is Audubon Everglades’ eBay administrator.

Comments are closed